Life:Moving

by Briony Campbell and the Life:Moving participants and project team

Life:Moving revolves around six films made by people affected by terminal illness as part of a collaborative participatory and research-based arts project. Over six months, through workshops and home visits, participants from John Taylor Hospice in Birmingham were given practical and critical training and support to develop and co-create their films. Working closely with filmmaker, Briony Campbell, and academic, Michele Aaron, different ideas, priorities and devices were explored and six films generated. The six films are screened at the NeMe Arts Centre, Limassol, but are also featured in a separate exhibition at the Materia Care and Rehabilitation Unit in Latsia, Nicosia.

Various questions underpinned this project. What were the most pressing issues for participants in making these films? Which film-making tool – a smart phone, tablet or SLR camera – would best serve their creative interests and practical needs? In the age of the selfie, how would individuals with a range of physical restrictions and a lot to say represent themselves and bring personal and often difficult issues to public attention? And how would the team support this and create an environment which respected the vulnerabilities of all those involved? Life:Moving’s broad aim is to challenge society’s misconceptions about terminal illness by giving those experiencing it the opportunity to tell their own stories, and by bringing these stories to a wider audience. In so doing, the project seeks to better understand the potential of digital film to serve the best interests of the vulnerable lives it so often depicts and then disseminates.

This potential, and the ethical praxis that harnesses it, is central to the research informing and informed by these films. While the digital age opens the world to all our gazes in newly connected and affecting ways, its sharing of human vulnerability is often rife with the same kind of objectifications and taboos long established in Western culture. This project sought to develop an ethical film praxis that communicates vulnerability in such a way as to forge human connection and empower its subjects, without compromise. In other words, without a retrenching of the invulnerable gaze that simply pities but remains untouched or un-humbled by the adversity of others. These are timely and pressing concerns, not least for arts practitioners and scholars, cultural theorists and community activists. Life:Moving is a powerful experience for all those it has engaged and testimony to the value of such projects for hospices, patients and the wider community.

Events

- Display at the Participation Matters exhibition

- Exhibition at Materia from 11.12.2017 to 31.01.2018, as part of the R! Festival (supported by Materia & IKME Sociopolitical Studies Institute)

- Workshop on 12.12.2017 during the R! Festival

Interview with Michele Aaron

By Olga Yegorova, on 15/11/17

Olga: You have been selected to take part in R! with a particular work, but what characterizes your art more in general?

Michele: I am a film academic. One of my areas of expertise is the representations of death and dying. Of my last two books, one was on the representation in contemporary mainstream cinema, another one on the representation of dying in visual culture. Indeed, I have always criticized the depiction of death and dying of mainstream narratives. I decided that, instead, I wanted to be involved in co-creating alternative types of representations which challenged and even countered the mainstream’s inaccuracies.

In this project, where I worked with the filmmaker Briony Campbell, it was very much about letting the participants lead. It was all about them, their voice, their needs, their wishes, their empowerment, their stories and stepping away from pretty inaccurate, misleading and sometimes even toxic representations of vulnerable people in society.

Olga: R! covers a variety of themes and concepts, where all projects relate to notions such as participation, democracy, community media and/or power, always in very diverse ways. From your point of view, which of these concepts play a role in your project?

Michele: Power is very important to the project as well as questions of politics and participation, given that the regular representation of death and dying is all about the power imbalances inherent in conventional practices of film. In fact, any art practice that is conventional and traditional frequently is based on an objectification, a dehumanization and a disregard of the dying but also of the frail. Human vulnerability is often diminished. The project was about challenging that. And to do so, it had to be founded in collaboration and participation where the research team worked together with the participants who were enabled to tell their own stories as much as possible.

When we say “participation,” we think of the individual participating in something “bigger”, in society. But actually, we might think of participation as being necessarily collaborative. It is not only the individual in relation to society but more importantly the individual in relation to another individual. Society consists, therefore, of collaborating participants. My project exposes the collaborative character of participation.

Olga: Are you arguing for a reconfiguration of the power relations between mainstream filmmakers and people represented in their narratives?

Michele: I think films can be a political art form for those who are the most disenfranchised, the least likely to be able to make films within the existing industries and traditions. Two of our participants were making the films with smartphones. None of them were using what we might think of as the most inaccessible technology devices that are available. They were using devices that were familiar or easy to use. This is essential because most of them did not have the skills or the strength to do anything fancier. In this way, film can definitely reconfigure power relations where it pertains to the representation of the most vulnerable within society.

New technologies allow the most vulnerable within society to tell their own stories, which is the only way to break out of the othering that most stories in whatever platform, channel or media reflect. Of course, that does not guarantee that the stories they tell will not be characterized by the problem of inequality or dogma, or whatever it might be, but it makes it less likely. The six films that we have are very different. But what I think they all do show, is an authentic voice, experience and an appeal to the truth that is theirs rather than imposed upon them.

Olga: Would this also mean that you want to defend another kind of society that is represented through your films where authentic voices from vulnerable people of society are louder?

Michele: My work is focussed on ethics. I see the potential of film to create a society in which ethical practice is common and that would mean that all our representations do not ground representation in othering and in power discrepancies, but rather through ethical connection, appreciation of human vulnerability and even, one could say, the ethics of love rather than hate. Yes, you can say that things would change then.

Olga: You mentioned that new technologies are a means to achieve this aim in your project. Do you think they do so also on a larger scale?

Michele: Absolutely, but they are also the means for the opposite because they allow precisely for the pervasive use and dissemination of imagery and stories that are entrenched with that sense of othering, making this aspect much more immediate and intimate as well.

Olga: You want to give voice to the “other”. But how do you prevent a situation where you take their place so that they still don’t get to speak?

Michele: Given that my participants are all physically frail and likely to die relatively soon, it is inevitable that I have to speak for them. We dealt with this by making sure the films speak for themselves as much as possible and that this was discussed openly during the process. Of course, the participants consented to my use of the films here at the Respublika! Festival, and in other events where the films are used to challenge conventional misunderstandings about the experience of death and dying and provide these important and honest self-portraits.

Olga: How important is the notion of empowerment for your work?

Michele: It is crucial. But I’d be wary of using it as well because the idea that someone is empowering someone else still keeps in place a certain power dynamic. I think that it is important to add that it was a collaborative and participatory project in which there was a sense of a shared vulnerability of all the people who were concerned in the making of the films.

Olga: How do you think that your project offers an alternative perspective on what media can mean for citizens?

Michele: The project’s emphasis on ethics is a no-compromise rule about what the films would or could be. The films had to emerge from the people concerned. In that sense, it is a case study for a citizen-led art practice for individuals with specific vulnerabilities. More than that, what I discovered in the process is that it has been immediately appealing to end-of-life-care-professionals and the end-of-life-care-system who were very interested in doing similar art projects in hospices or hospitals. The films are very illuminating because of the ways they reveal quite interesting things about their clients’ experiences on the care and about what it’s like to be terminally ill. They entail a strong educating value for the staff of hospices.

Olga: Why is it important to offer a citizen-led media outlets?

Michele: The most obvious reason is the misrepresentation of the physically fragile. It a way to contribute to overcoming the discrimination and trauma that people affected by terminal illness experience because of the absence of other narratives.

Then, there is a practical reason in terms of society’s economics. A change in the attitude towards illness and dying can help to address problems that emerge on a broader scale due to financial crises and the question of how to deal with the ill or dying proportion of the population.

But we saw also clear ‘internal’ benefits, which we anticipated as the project was designed in partnership with the psychotherapist at the hospice so that the participants were supported by, and working with, the therapeutic potential of this art project. The majority of the participants found it enormously beneficial, on a variety of levels. For one of the participants, it countered “the sheer monotony and boredom of dying” as he put it. For the woman who uses the eye gaze technology, it was an amazing opportunity as she made the film with her son who is really interested in filmmaking and it allowed them a wonderful opportunity to spend time together and do something really constructive and meaningful.

Work at Respublika!

We’re all terminal

Complexities of care

Rob’s Portrait

Fran and Louis

Keisha

Yussef and Haifa

Andrew Burchell

Andrew’s enthusiasm for the project came from his long-standing interest in art and culture, strong views on life and death and the very limited opportunities he has for social or creative activities owing to significant physical constraints. Unexpected hospitalisations during the project presented further obstacles to realising all his aims for the film, but in collaboration with friends, Briony and the research team, images were selected and monologues captured and brought together into two final cuts.

The challenge here was about achieving a balance between Andrew’s ambitions for the project, his wealth of ideas and what was possible.

The final result was achieved primarily through Briony visiting Andrew at home, and recording him there with a digital SLR camera. Though Andrew wasn’t able to be as involved in the project as he had hoped, his characteristic optimism – his friends from his time living in Kenya pronounced him a ‘life-ist’ – compelled him to give what he could. We recorded his thoughtful reflections on his experience of the care system and the heightened value that medical advances place on human life.

Keisha Walker

Keen to learn new things, Keisha was determined to take part in the project. Like some of the other participants, however, she found the process of filming and being filmed more exposing than she had anticipated. As a result, it took time to find the tools that suited her and allowed her to say what she wanted to say and in a way that was both comfortable and authentic.

Interested, originally, in conveying her particular perspective as she moved through her world in a wheelchair, a GoPro seemed the ideal tool for her to either wear or attach to her chair. However, it proved too fiddly to mount or film with. Alternative solutions were required: the familiarity of her smart phone camera was revived through a Samsung tablet, and its intimacy through a high quality sound recorder to provide audio.

A variety of technologies enabled Keisha to capture a range of her ideas and perspectives, and these have been worked together for the exhibition.

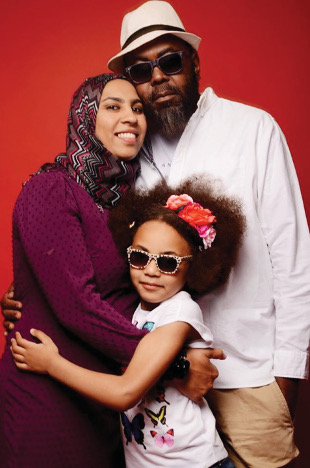

Yussef and Haifa Ahmed

The film, ‘The inspirational man and his Journey to one’, is a collaboration between Youssef and his wife, Haifa, and Briony. When the project started, Yussef was already very close to the end of his life and would die shortly afterwards.

Haifa attended some of the early project workshops and she and Yussef had a keen sense of what they wanted the film to show; that it might reflect his beliefs and experiences through highlighting his musical and political activities and at the same time provide an important record for their daughter Reem.

The challenge of this film was to find the right balance between the authorship and hopes of those involved in its creation and respecting and privileging the wishes of Yussef. The film combines old and recent photographs and footage of musical performances, Yussef’s final birthday and his funeral. It provides one of the narratives to emerge as part of his involvement in the project. Due to losing Yussef so early on, we were reluctant to fix his story without him. Therefore, in addition to presenting an edited film on the central projector, other clips and recordings, which were produced or selected by Yussef and Haifa as part of the project, are available on the touchtable. In this way, other narratives about Yussef might emerge through your interaction with it.

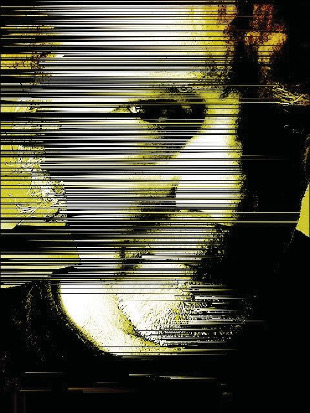

Robert Homer

Rob is a keen artist and, more recently, poet. No stranger to the creative process, Rob’s challenge was how to transfer this familiarity to the unknown medium of film and via a set of tools that were new to him. His priority was a ‘warts and all’ disclosure of his experience of cancer. In order to achieve this, he started by filming on his phone last thing at night and first thing in the morning, his worst and best times of the day. This hand-held recording captured the intensity and intimacy he was after but the quality was poor. These monologues would develop into the core of his film, but Rob went on to experiment with a higher quality SLR camera and time-lapse photography to provide other layers to his narrative of self-portraiture.

Peter

Peter’s approach to the project was shaped by his long-term love of both hiking and photography. He was clear from the start that his film would be focused on these, and on invoking a sense of what he most missed doing now. He recorded a voice-over and edited it together with his selection of photographs he had taken in the past to create a slideshow of landscapes that have influenced his character and offered him sustenance throughout his life. No longer being able to visit them, this film serves as a tribute to what they have given him. Unlike most of the other films in the exhibition, Peter recorded and edited his film independently.

Fran Tierney

Fran’s project is especially, and inevitably, indebted to technology. She uses Eyegaze, an eye-operated communication system, to speak having lost the ability to use her own voice due to Motor Neurone Disease. But, as she pointed out in our first workshop, this computer-generated voice has no emotion. The challenge, then, for her and her aspiring-filmmaker son, Louis, was about how to fulfil Fran’s wish to convey her feelings about her diagnosis and the implications for her family.

During a workshop that they attended together, Fran and Louis were introduced to the idea of using old photographs as a backdrop to storytelling. This proved a fruitful way for the family to engage with the project and to gather material that, together with footage taken by Louis, would become the visual accompaniment to the text that Fran wrote. The film was a collaboration between mother and son. Fran and Louis worked mostly independently: Fran on the script and Louis filming and editing.

Workshop and exhibition at Materia

(Photographs by Nico Carpentier)

(Photographs by Nico Carpentier) Extra material

Brochure on Live:Moving

Life:Moving Poster