Social Sculpture Performance/Workshop Unfolding-Unwrapped

Creation draws a line between being a passive and an active agent in people’s life. Creation starts with questions. This process of discovery is both exceptionally broad and incredibly relevant for creating strong contextual work and social behaviour; regardless of whether we are conceiving of socially engaged performative art work or a highly sophisticated installation.

Particularly, the sequences of the workshop/performance focus on human behaviour in a group and as individuals. The workshop confronts the participants and audience sometimes in a real, sometimes in a metaphorical manner with situations of Conflict-Confrontation-to be on your own–against each other. However, the way the sequences of the workshop/performance are structured also leads to reflections about solutions, in order to find ways of collaborating and creating a democratic process.

Nevertheless, the political situation and state of the world is quiet far removed from a culture of collaboration and strong democracy. Not only distant politics and politicians are important for us, so that we become aware of conflicts and confrontations, our loneliness or powerlessness. At the same time, being creative and willing to act collaboratively, in democratic ways, in order to overcome conflicts, is crucial, regardless of whether these are enacted in our own daily lives and environments, or on the political stage.

Social sculpture is part of the concept for my personal project, but at the same time, it is implemented in interactive and participative workshops for the general public/audience. I add my own ideas and concepts, as well as the keywords “Conflict”, “Confrontation”, “Collaboration”, and “Democratic process”.

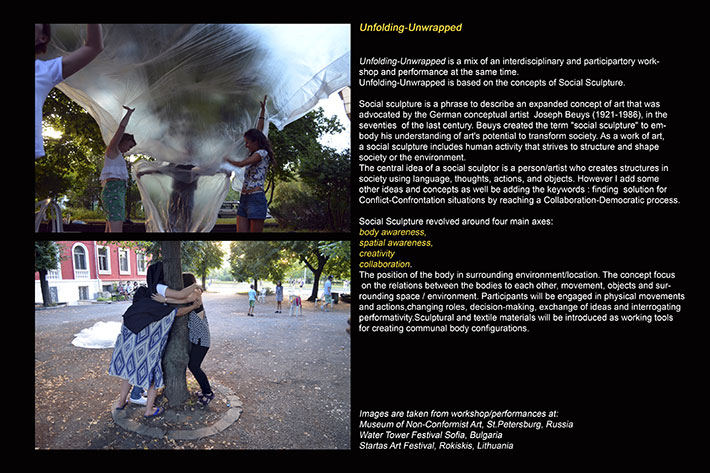

Social Sculpture revolved around four main axes: body awareness, spatial awareness, creative awareness and collaboration. Social sculpture is a term to describe an expanded concept of art that was advocated by the German conceptual artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), in the seventies of the last century. Beuys created the term social sculpture to embody his understanding of art’s potential to transform society. As a work of art, a social sculpture includes human activity that strives to structure and shape society or the environment. The central idea of a social sculptor describes a person/an artist who creates structures in a society, using language, thoughts, actions and objects.

The position of the body in the surrounding environment/location is vital. The concept focuses on the relations between bodies to each other, movements, objects and the surrounding space/environment. Participants are engaged in physical movements and actions, changing roles, decision-making, exchange of ideas and interrogating performativity. Sculptural and textile materials are introduced as working tools for creating communal body configurations.

Events

- Performance on 9.12.2017 during the R! Festival

- Performance on 11.12.2017 during the R! Festival

- Performance on 13.12.2017 during the R! Festival

- Performance on 15.12.2017 during the R! Festival

Interview with Johannes Gerard

By Olga Yegorova, on 18/11/17

Olga: You have been selected to take part in R! with a particular work, but what characterizes your art more in general?

Johannes: While the workshops for R! have a particular focus on the participation of the audience, many other videos, installations or performances that I do are more individual. In most of my work, I use a metaphorical style that offers interpretations that are alterable and never set in stone. I do not blurt out straight political statements. Sometimes, it is very difficult to see which statement I am making. You, as the audience or participant, have to think about it and there is always more than one interpretation. Interpretations are never fixed anyway.

Olga: R! covers a variety of themes and concepts, where all projects relate to notions such as participation, democracy, community media and/or power, always in very diverse ways. From your point of view, which of these concepts play a role in your project?

Johannes: Participation and collaboration play the most important roles in my project. And then, it is about establishing a democratic process since the participants of my workshop need to find ways to work together. My project deals with conflict, the individual in a group and the process of finding ways to collaborate with other and finding common solutions that help to move forward.

Olga: You just mentioned that the individual finds himself/herself in the context of a group. How do you work with the relationship between individual and collective and what does that stand for?

Johannes: I have been doing this performance many times in different countries and it is never the same. Every group has always a different dynamic. People mostly start as individuals; sometimes being complete strangers to each other, sometimes knowing each other from before. At first, I just make them walk around, they have to first cross each other’s ways as individuals. Then, they have to pair up, while one person leads the other one, whose eyes are covered. And later I divide them into groups. In this process, I involve objects that are used with as well as against each other.

When I did this workshop with five women in Russia, for example, I was very surprised because the women were quite aggressive towards each other at the beginning. They started to fight very seriously with the chairs. As I slowly lead them to work together as a group, the tension decreased. In Lithuania, in contrast, as the women of the group knew each other from before, the fights with the chairs were not as brutal. They kept their distance, without wanting to hurt each other. So the tension between the individuals and the group varies a lot.

Olga: Do you think that there is a wider societal or democratic interpretation of the different ways that groups and individuals act in your workshops?

Johannes: It reflects certainly a democratic process when it comes to making decisions on what to do next and how to do it. At some point, the participants have to make decisions as a group about how to move and in which direction to go. Thereby, it is important to me to avoid situations where one person takes the lead. Otherwise, I may have to intervene. To give an example, while the Russian group was good at spreading the power to decide among each other, in Lithuania, pre-set dynamics of the friends’ group made it hard to avoid leading characters. They instantly wanted to hand over the power to decide to one person. This changed also my role. I had to encourage everyone stronger to have an own opinion.

The democratic dimension is here not obvious, but I aim at making people reflect on this in the aftermath, asking them about their thoughts on the workshop. I do not just stand there as the big artist, making a great project that you have to like, but I also ask for critique. I give something being prepared to receive reactions from the participants. To me, this strongly resembles democracy.

Olga: Your project seems to highlight the importance of the sensorial forms of expression. How does the sensorial experience work in your project and why is it important to you?

Johannes: The sensorial experience of my project is important as it aims to make the people get a feeling of their body and their environment. Thereby, I do not just mean the room you are yourself moving in, but most of all, your social environment and the other bodies surrounding yours.

Olga: What happens with the spatial environment and its daily objects as you start using them? Do you transform their meanings? And if so, what do you want to achieve through this transformation?

Johannes: I use objects in order for awakening peoples’ own creativity, their fantasy. When you see a chair, you usually just think of it as something you can sit on. But I ask the group to do something crazy with the chairs: walk on them, fight with them, whatever comes into their mind. It is very important to me that people open their minds and become creative with daily objects and explore that there are many more things you may use them for. The ropes serve to make a space, own borders and limits visible. At the same time, they can serve as a bounding factor that the group uses to tie each other together. Many of these objects become symbols of working against each other and finding ways of moving in the same direction in more harmonic ways.

Olga: In your performance, the distinction between performer and audience collapses, at least to some degree. The citizen becomes also an artist. Is this correct? And if so, why does that matter?

Johannes: Maybe you are not Picasso or Matisse, but everyone has creativity. And art is a very important means to discover your it. This creativity can then also serve you, in order to overcome the daily conflicts that you encounter. My role is to encourage the participants to revive their creativity. Thereby, depending on the group I am working with, I let go of my guiding power because the people develop own ideas. But some groups are completely lost if you give them too much freedom. And then, although that does not resemble my character normally, I have to become more strict and play the teacher role to ultimately make everyone explore their own artistic vein.

Olga: Can this experience be translated into how democratic processes can be enabled?

Johannes: In a democratic society you have lots of individuals with conflicting ideas, where people have to find solutions, or at least ways to live with each other despite those differences. This connection is not something that you come up with just participating in the workshop, but only through your own reflection. To me, it is crucial that everyone involved asks her-/himself: Why am I doing what I’m doing?

Olga: Do you see your workshop then also as a means of empowerment?

Johannes: I can only speak of empowerment if there is an independent reflection that the participants develop. This happens in workshops with kids who do not necessarily do what I tell them to do. They are empowered because they take the power to disobey. It is empowering when a person tells me that he/she does not like to do certain things instead of treating me as the master. If I do something, I assume that not everybody likes it. And if someone tells me that an exercise is very stupid, at least I empower the person to have their own opinions and to dislike things. This is why workshops may go very well, but they can also end up being a complete disaster. And that’s ok.

Work at Respublika!

Workshop 1 (9 December 2017 in Limassol)

(Photographs by Olga Yegorova)

Workshop 1 video by Olga Yegorova

Workshop 2 (11 December 2017 in Limassol)

(Photographs by Olga Yegorova)

Workshop 2 video by Olga Yegorova

Workshop 3 (13 December 2017 in Nicosia)

(Photographs by Hazal Yolga)

Workshop 4a & b (15 December 2017 in Nicosia)

(Photographs by Orestis Tringides)

Workshop 4b video by Orestis Tringides

Earlier work